Imagine all the people

As I write this, the US population is on the verge of breaking 300 million. In fact, the Census Bureau estimates that we'll hit the magic number at 7:46 AM EDT tomorrow morning. The last time the country broke a hundred million mark, it was 1967. (That would be 7 years before I was born.)

As I write this, the US population is on the verge of breaking 300 million. In fact, the Census Bureau estimates that we'll hit the magic number at 7:46 AM EDT tomorrow morning. The last time the country broke a hundred million mark, it was 1967. (That would be 7 years before I was born.)While many are taking the opportunity to discuss America's consumption patters, resource usage, and immigration policies, an interesting article showed up on New Scientist today. What would happen to the environment, the world, if the human species just up and left? How long would the traces of human habitation last on the planet?

As you can imagine different aspects of the human footprint would disappear at different rates. It's actually a fascinating study in entropy (roughly, the tendency of a system to go to the least energetic state - to just fall apart - when there's no one to maintain it). There's a couple of ways of looking at this article. First, the glass-half-full argument: that in spite of how much we've done to the planet, none if it is totally irreversible, that if left to its own devices, nature will take care of her own. Then there's the glass-half-empty argument: that it would take 100s to thousands (in the case of nuclear waste, maybe even millions of years) to undo the damage we have done.

You can read into it what you want. Me, I like the idea that things can bounce back. But, if we were to turn everything off right now, would the environment, the ecology turn out exactly the same? No, of course not. The environment probably didn't return to an exact pre-Ice Age state after the glaciers melted, either. Once an ecology is altered, artificially or naturally, I imagine it's nearly impossible to return it to its native state. However, the resilience of nature is amazing. You can see it just by looking at a vacant urban lot, and see the grass, weeds, and trees taking it over. Nature will grow back where it can.

But that doesn't mean we shouldn't still be careful what we do.

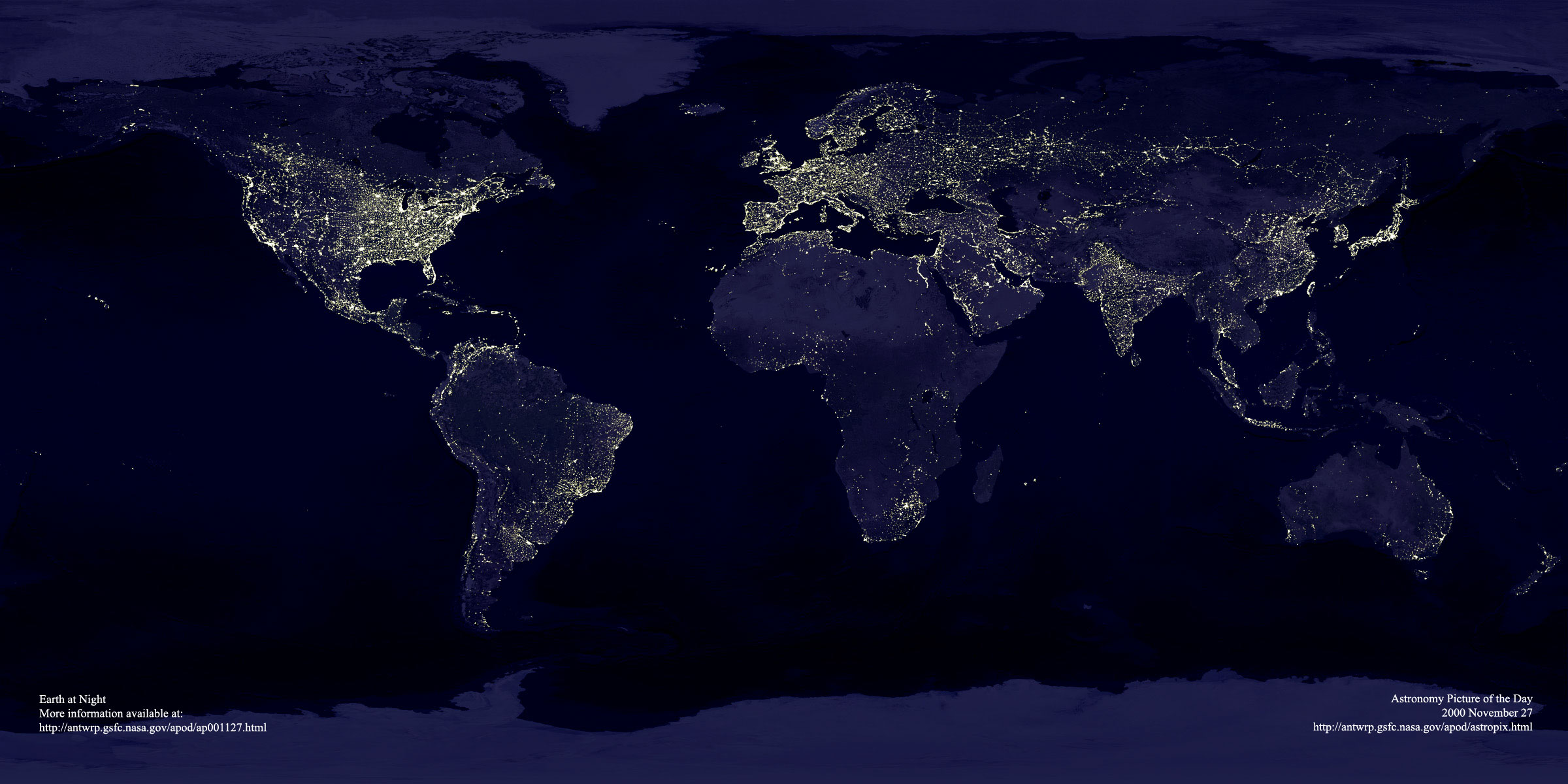

[See New Scientist for the global exit story. To see how close the US is to the 300 million mark, see the Census Bureau's population clock. Most likely, by the time you read this, the zeros will have turned over. "Earth at Night" courtesy of NASA's Astronomy Picture of the Day.]